The following is a story I heard a few years ago:

I heard about a man who was standing in the middle of the Golden Gate Bridge, admiring the view, when another tourist walked up alongside him to do the same. And he said: ‘I heard him say quietly as he took in the beauty of the view: “What an awesome God!” I turned to him and I said, “Oh, are you a Christian?” He said, “Yes, I am a Christian.” I said, “So am I,” and we shook hands.

I said, “Are you a liberal or a fundamental Christian?” He said, “I'm a fundamental Christian.” I said, “So am I,” and we smiled and nodded to each other.

I said, “Are you a covenant or dispensational fundamental Christian?” He said, “I'm a dispensational fundamental Christian.” I said, “So am I,” and we slapped one another on the back.

I said, “Are you an early Acts, mid Acts, or late Acts dispensational fundamental Christian?” He said, “I'm a mid Acts dispensational fundamental Christian.” I said, “So am I,” and we agreed to exchange Christmas cards each year.

I said, “Are you an Acts 9 or 13 mid Acts dispensational fundamental Christian?” He said, “I'm an Acts 9 mid Acts dispensational fundamental Christian.” I said, “So am I,” and we hugged one another right there on the bridge.

I said, “Are you a pre-Trib or post-Trib Acts 9 mid Acts dispensational fundamental Christian?” He said, “I'm a pre-Trib Acts 9 mid Acts dispensational fundamental Christian.” I said, “So am I,” and we agreed to exchange our kids for the summer.

I said, “Are you a twelve-in or twelve-out pre-Trib Acts 9 mid Acts dispensational fundamental Christian?” He said, “I'm a twelve-in pre-Trib Acts 9 mid Acts dispensational fundamental Christian.” I said, “You heretic!” and I pushed him off the bridge.

I like this story because it highlights how divisive people become over the smallest of differences. While most people in a congregation may agree on core beliefs, there will always be outliers, rebels, and those who think differently. Most congregations are sensitive to these differences even though they vary in the degree to which they react to these differences. Sometimes a congregational leader is the one who takes a position that is different. When the congregation is rigid in their beliefs, leaders will find it difficult to take a different position on important issues.

This recent election is a good example. I have heard from a number of clergy about how difficult it is to take a specific position in response to a statement made by a political leader. When they speak up, it creates problems for others in the congregation. They are accused of stirring the pot.

One of the tragic failures of seminary education is the unwillingness and inability of seminaries to train students in emotional process. I consider it reckless for seminaries and educators to push students to be more prophetic in their local congregations without first preparing them on how to handle psychological push back and resistance in productive ways.

What does it look like to take a stand in a congregation?

Taking a stand is the result of many weeks, months, or even years of grappling with an issue. Taking time to reflect and think about a particular issue can generate key questions that lead to a broader awareness of the problem and possible solutions. Without a disciplined effort, congregational leaders run the risk of being focused on the wrong questions. Questions like:

- At what point do I take a stand?

- Do I wait and see how this will play out in the congregation before saying something?

- Do I preempt any conflicts by making a statement?

- Do I spread information about something to key leaders in the congregation in an attempt to do damage control?

These questions reveal a deep fear of the relationship system. Worry can take over as one’s focus is on how others will react and not on one’s beliefs and core principles. Being anxious about the reaction of others stifles one’s ability to represent oneself and one’s best thinking about an issue. I’m not suggesting that we not pay attention to the relationship system. Indeed, understanding the relationship system is the first step to being a good leader. Problems arise, though, when the temperature of the relationship system determines how one responds to the system.

What is an emotional process?

Dr. Murray Bowen observed that in the family there is an emotional oneness. In his research with families where an adult child was diagnosed with schizophrenia, he writes, “The ‘emotional oneness’ between mother and patient (child) was more intense than expected. The oneness was so close that each could accurately know the other’s feelings, thoughts, and dreams. In a sense they could ‘feel for each other,’ or even ‘be for each other.’” (Family Therapy in Clinical Practice, 72).

Bowen concluded that the process he saw between the mother and child with schizophrenia was a process that was active in all families at varying levels of intensity. Wait. It gets better. Bowen concluded that it no longer made sense to diagnose individuals with schizophrenia. Instead, he saw schizophrenia as a symptom of the larger family emotional process. It was as if the whole family had schizophrenia. For Bowen, the problem was in the family as a unit, not in individual members of the family. The individual members were simply the symptom bearers.

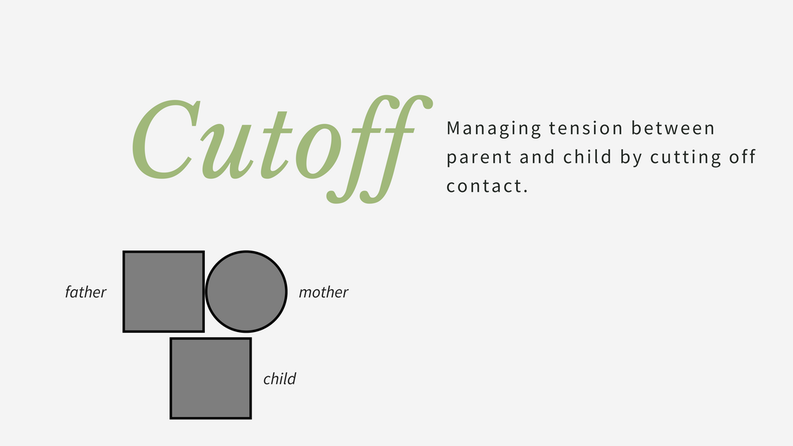

As congregational leaders (like everyone else) we are susceptible to the subtle and not so subtle pulls towards emotional oneness. As anxiety rises in the system, differences are seen as a threat to the well-being of the group and individuals automatically become reactivity as a way to get people back in line. It includes engaging in conflict, avoiding or distancing from others, taking over responsibilities for others or having someone take over your responsibilities, or identifying a child (or a vulnerable member of the group) and diagnosing them. You can learn more about this by clicking here.

This effort towards oneness also plays out internally. When we encounter others who think, feel, or act differently from the way we think, feel, or act our brains move towards an emotional oneness. That is to say, our feelings, thinking, and acting can fuse together. It can be difficult to tell the difference between our thoughts and our feelings. In fact, our thoughts can be hijacked by our feelings. Our body language, vocal intonation, and eye contact may shift to represent our feelings about the other person.

The point of all of this is that we can get caught up in a life force that moves us towards togetherness in the relationship system. Our fears can get the best of us. Being an effective leader requires an awareness and understanding of the emotional process, seeing it at work in our relationships, seeing how one contributes to problems in the relationship system, defining oneself based on these observations, and taking action steps.

Defining a self

Taking a stand is NOT about:

- debating a point.

- convincing others one is right.

- marshaling people together to outvote or outmaneuver someone else or another group.

- protest.

- viewing others as stupid, uninformed, uneducated, misguided, incapable, or prejudice.

- sharing one’s feelings.

- feeling lonely.

Taking a stand IS about defining a self.

1. Defining a self is recognizing the trajectory of maturation.

From birth to adulthood, all of us are developing towards being a self. At birth we are completely dependent on others for survival. Over time, our dependency changes as we develop the capacity to think, feel, and act for self. As we age, we continue to stay connected to those who raised us, while differentiating from them at the same time.

2. Defining a self is the ability to separate thinking from feelings.

Bowen wrote: “The core of my theory has to do with the degree to which people are able to distinguish between the feeling process and the intellectual process . . . We found that there are differences between the ways feelings and intellect are either fused or differentiated from each other, and this led us to develop the concept of differentiation of self. People with the greatest fusion between feeling and thinking function the poorest. They inherit a high percentage of life problems. Those with the most ability to distinguish between feeling and thinking, or who have the most differentiation of self, have the most flexibility and adaptability in coping with life stresses, and the most freedom from problems of all kinds. Other people fall between the two extremes, both in the interplay between feeling and thinking and in their life adjustments.” Family Therapy in Clinical Practice 355.

3. Defining a self is about taking an “I position.”

Bowen wrote: “The differentiation force places emphasis on “I” in defining the foregoing characteristics. The “I position” defines principle and action in terms of, “This is what I think, or believe” and, “This is what I will do or will not do,” without impinging one’s own values or beliefs on others. It is the “responsible I” which assumes responsibility for one’s own happiness and comfort, and it avoid thinking that tends to blame and hold others responsible for one’s own unhappiness or failures. The “responsible I” avoids the “irresponsible I” which makes demands on others with, “I want, or I deserve, or this is my right, or my privilege.” A responsibly differentiated person is capable of genuine concern for others without expecting something in return, but the togetherness forces treat differentiation as selfish and hostile.” Family Therapy in Clinical Practice 495.

4. Defining a self is about anticipating reactivity from others when one takes a stand.

When one takes a stand, one will most certainly experience push back from important others. The push back is an indicator of the level of togetherness in the relationship system. Togetherness by its very nature impinges on one’s ability to think, feel, and act on one’s beliefs and convictions. Bowen observed the predictable nature of reactivity when one defines a self. Reactive others will say: You are wrong . . . You are wrong, change back . . . You are wrong, change back, or these are the consequences. Anticipating reactivity by strategizing a way to respond to it helps one stick to their effort of differentiation and not give up or give in to the togetherness pressures.

5. Defining a self is about containing one’s reactivity

The emotional system is an automatic, reactive system. It does not require thinking in order to function. At its core, it is responsible for keeping the human alive, healthy, and safe. However, when tension in the relationship system goes up or becomes chronic, the emotional system struggles to differentiate real fear from perceived fear. So, even when we are making an effort to define a self, we can become internally reactive to our efforts. The thinking system can downregulate this process, but it requires an awareness of how one typically reacts when tensions are high. Developing a strategy by using the thinking system will be a counterbalance to this effect.

6. Defining a self is about keeping fear in check

One of the most helpful discoveries I made early in ministry was the following: when others object to a position I take, they are not reacting to how I think, but how my thinking impacts the relationship system. When anxiety is high, when people are afraid, there is a herding phenomenon where any action, belief, or thought that is different from the group's actions, beliefs, or thoughts is perceived as a threat to the group. Perhaps you’ve heard the phrase, “you are either with us or against.” There is no factual basis for this phrase. It’s a lie. It is possible for people to think, feel, and act differently without putting the group at risk. In fact, groups function better and are more adaptable when individuals are able to do their best thinking.

One last thought

When an issue that is controversial comes forward, it is an opportunity to define one’s thinking about it. If one hasn’t thought much about the topic, then sharing this information is also a way to define a self. It is not the position one takes that is important. It is the way one defines oneself in the midst of anxious others. Taking a stand is about knowing when one is reacting to others and when one is representing self to others.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed