At a recent gathering of the General Conference of the United Methodist Church a majority of delegates voted to uphold the denominations stance against homosexuality and establish additional penalties for bishops and clergy who violate its Book of Discipline. In response, congregations on both sides of the issue are having conversations about whether to remain in or exit the denomination. I invited Richard Blackburn, the Executive Director of the Lombard Mennonite Peace Center, to talk with me about how leaders in the church might navigate this current reality.

John Bell: There is a lot of reactivity going on right now in response to the decision of the General Conference. I wanted to have this conversation with you because I think there are ways of thinking about this challenge that can be useful to congregational leaders. The first question I have is more of a general question. What makes it difficult for individuals to maintain a relationship when they disagree about issues that are important to them?

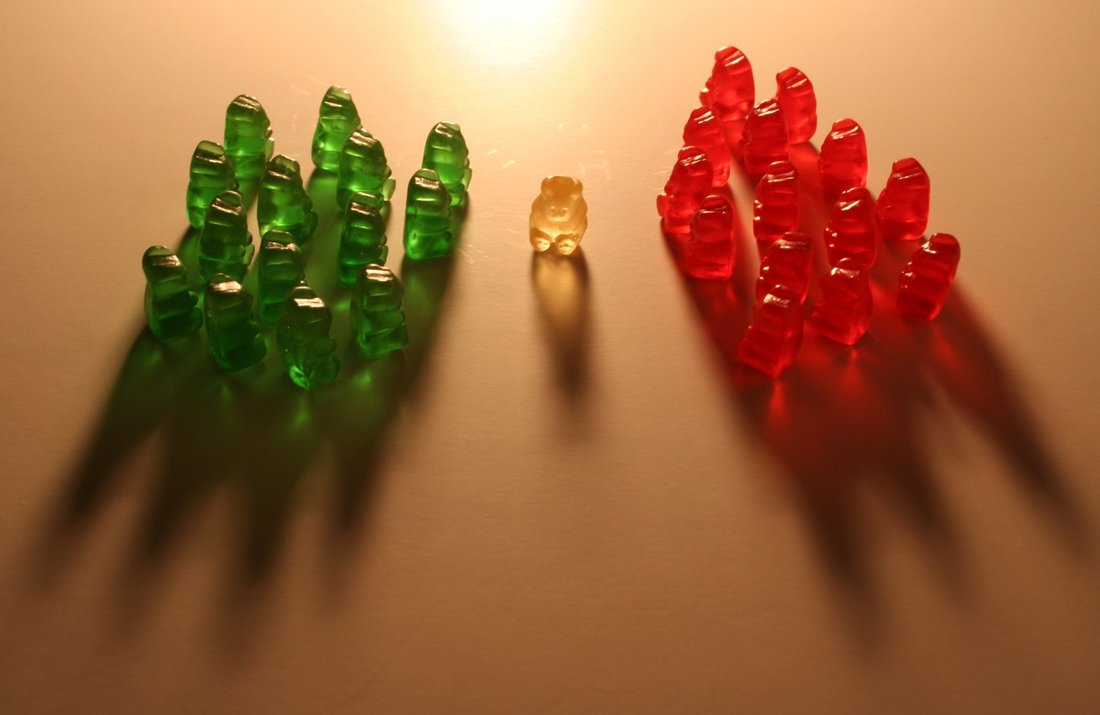

Richard Blackburn: I'm sure there are a number of things that contribute to that. In general, many people get their identity from the perspective they take on particular issues and they can get into a defensive mode that creates polarization. It’s that polarization, accompanied by reactive ways of stating one's perspective, that further divides. The relationship itself seems to be put on the back burner. That’s more of a general kind of response to the question.

But, one has to also look at what people are bringing from their own family of origin that prompts them to move so quickly into that defensive, reactive mode. That’s going to be different for every individual. I would also wonder what people are bringing from the chronic anxiety within the congregational system that gets projected onto the way people debate these issues. Certainly, societal anxiety is having an impact as well. As we’re living in a time of societal regression–and that's just one of the signs of the regression—it makes it difficult for people to talk about differences in a way that helps them to maintain connection. We get into a rigid way of defending our perspectives that just further fosters the polarization.

JB: What are congregations going through that you think gets projected onto this struggle?

RB: I think the broader societal anxiety is impacting congregations. The people in United Methodist churches have seen membership decline over the last number of decades. There's an increasing fear for some churches about whether they’re going to survive. That certainly jacks up anxiety. So, if you’ve got an issue around which you have polarization, fear can lead toward further defending the differing perspectives. The fear is that, if we go with your perspective, more people are going to leave the church. If they leave, it's all your fault. The blaming gets in there.

Along with the blaming are ad hominem attacks to the personhood of others. Then the anxiety spreads through all the triangles. This is going to be different in different churches given the level of chronic anxiety within the church and given the different histories they have. Some churches have high levels of chronic anxiety because they have a backlog of unresolved things from the past that have never been addressed in a healing way. Other churches may have less chronic anxiety but are still vulnerable to picking up the anxiety from society and projecting it onto the church.

JB: How would you define the problem facing United Methodist clergy and congregations who don't support the denomination's position, who find themselves on the outs and are trying to figure out what to do? How would you define that problem?

RB: I think the most immediate problem, if you can put that word with it, would be to not go into an immediate reactive mode but to step back from the anxiety as much as possible. To really think about, how can we approach this in an objective kind of way that is not being fueled by the anxiety? What is our collective self-definition? How do we pursue this in a non-reactive way? It is recognizing that there are others who have differing perspectives. How do we work at this in a way that is trying to stay emotionally connected with those who have differing perspectives? No doubt, in many of these churches, there are going to be people who are on all sides of the issue. It’s got to be approached in a way that doesn't further divide the congregation. So, I guess the basic question is, how do we work at this in a way that tries to identify the legitimate interests that all parties have and then work at coming to some kind of understanding whereby we can each believe what we believe without it creating further division? How do we work at staying connected given the diversity that's within the church? How do we relate to others who have different perspectives than our own in a way that still values that common ground that we have in Christ? How do we work at this in a way that approaches others with a different perspective out of a posture of genuine curiosity? Not to bait. Not to get into a polarization. To really try to understand the differing perspectives and see if we can come up with a win-win whereby we are honoring the legitimate interests of all parties to the point that we can still stay in ministry together.

JB: Two years ago, the bishops set up a process where various people from around the denomination worked to come up with a plan. It was clear, though, when they had concluded, they were not in agreement. So, the bishops put forward one of the plans and then tried to persuade everyone to get on board with it. You mentioned how important it is to identify the interests each is bringing to the table. I’m not asking you to be critical of the process but I'm just wondering if what happened reflects the process that was used or is it a sign of the regression being fueled by the anxiety in the church? My observation is that evangelicals and progressives don't really know how to talk to each other in constructive ways. I wonder what you think about that.

RB: I really don't know enough about the process to be able to comment intelligently on it. They didn't ask me to come in and mediate [laughter]. If I had been asked to come in and consult with them, I would have begun by getting an agreement on procedures so that the process was very clear from the beginning and that all parties were committed to following the process. I would start with information gathering to document the full range of interests. Then there would be education to help people understand what healthy conflict transformation looks like and help them understand how churches function as an emotional system. It would include steps that work at healing unresolved hurts from the past. Then we would work at creative win-win problem solving. I don't know to what degrees any of this was done but this would have been the kind of process I would have recommended.

However, given people's proclivity for polarization and reactivity, there is no guarantee that they could have come up with a win-win because people do tend to get rigid, inflexible and locked into their positions. I would hope that working at some degree of real deep listening to one another, and the hurts that people have experienced, would clear away some of the chronic anxiety from the past—which is part of what's behind some of the reactivity—to the point where they would have been more open to coming to some genuine win-win proposals.

JB: I was thinking about how in the family one doesn't have to go back in history to relive the patterns because they're always present in the system today. In congregations it can be different because it's not really a family per say. Experiences can generate chronic anxiety which we bring forward with us into the present. In terms of conflict resolution, you are saying that there needs to be a redress of those things. How do you think about that in terms of not getting focused on feelings but using feelings to identify how to move forward with thinking? How do you separate these things out?

RB: Well, I'm not entirely sure. Obviously, it's pretty complex. When I'm working with a congregation, the hurts from the past that have never been addressed in a healing way have a way of leaving residue so that, when there is some moment of acute anxiety in the current situation, the reactivity is blown out of proportion because it's being fueled by that chronic anxiety from the past. When I'm working with a congregation, I'm trying to surface those unresolved things from the past in a neutralizing history context that helps people who have experienced these hurts to express them in non-blaming ways. It's preceded by the education phase. They've learned about how hurts from the past can be expressed in ways that are not coming out of the reptilian brain, how to put things in terms of "I" statements and how we are impacted by situation. Instead of reacting in a blaming way, we’re taking the raw emotions of hurt, whatever that might be, and putting it into words that are describing rather than acting out the feelings. It’s putting those emotions through the neocortex and putting them out there in a non-reactive way to help the other person really listen. It’s about understanding the impact that that past situation has had on the person sharing the hurt. I think it is a way of putting the feelings out so that people really connect with each other, listen to one another, and ultimately let go of those hurts from the past. Then they can focus on the question of how we're going to address the current concerns in a more genuine problem-solving way that is respecting and honoring of the diversity of perspectives that are there.

JB: There are a lot of clergy and congregations on both sides of the issue who are discerning whether to stay in the denomination or exit. It’s more than just a question of do you stay or do you go. It’s a complex discernment process. Are there ways of thinking about it from a systems perspective that's helpful?

RB: Again, I would say step back from the immediate reactivity so that one is doing this out of principles, values and beliefs. Think about what it would look like—if the decision is to go towards separating—and how that can be done in a differentiated manner. How can it be done in a way that is grounded in principles, values and beliefs and in a way that is not stirring up reactivity? How can it be done in a way that is still staying connected to those who may have a different perspective? The last question you asked goes in the same direction. If the decision is to leave, how can it be done in a thoughtful way? It would be interesting to think about ways of staying connected even though one decides to leave. Are there ways of affirming what we still share in common? Are there ways that we can still cooperate on certain aspects of our broader mission so that it's not just a complete cutoff but still has a commitment to ongoing relationship.

For instance, if a church should actually split over the issue, how can that be done in a way that is blessing each other on our separate journeys and not done in a blaming, rancorous way. Keep in mind that to bless in Latin is benedicere which literally means “to say good things.” So, how can we say good things about one another even though we've chosen to go our separate paths? Are there, again, aspects of our common mission that we can still cooperate on? Maybe there is a community ministry that the church had been involved in. Can we commit to both continuing to be involved in that particular community ministry? Or maybe we can work together to have a joint youth program. Or something like that. What are ways of staying connected even though we've decided to separate?

The Lombard Mennonite Peace Center provides resources on a diverse range of peace and justice concerns, from biblical foundations for peacemaking, to conflict transformation skills for the family, the church, the workplace, and the community. They also have become a nationally recognized ministry for training church leaders in understandings grounded in family systems thinking via the Clergy Clinic and the Advanced Clergy Clinic in Family Emotional Process. Additionally, LMPC is called upon to help those caught in difficult conflict to find reconciliation and healing by offering mediation services for individuals, churches, and other organizations. For more information, go to lmpeacecenter.org.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed