I wrote this blog in the hope that I might clarify for myself what a discipleship program looks like in a higher functioning congregation. In the Christian church, a discipleship program is a process by which a congregation teaches children and adults the shared beliefs and values of the congregation. This blog took several twists over the last few weeks as I thought about discipleship. What I’m publishing here for you is not a conclusion but my reflections on the intersection of beliefs and relationships. There is more to think about, and I will more than likely keep writing about it. It’s worth a closer look.

All congregations, regardless of their faith expression, provide religious education. The shared beliefs and values of the congregation are passed on to children and adults. From within this educational system, leaders emerge who teach and train other children and adults the shared beliefs and values of the congregation. This process works well until individuals question these shared beliefs and values or promote ones that are contrary.

For congregations that promote independent and critical thinking, there is an inherent risk that such an effort may create problems for the congregation. As leaders grapple with this dilemma of how flexible they will be in the face of different beliefs or values, they may become stuck in an emotional process.

If you have ever tried to hold a belief that is contrary to the congregation you belong to, you have probably experienced this emotional process. You can “feel” the tension that is created both internally as one grapples with separating thoughts from feelings, and externally as one tries to navigate the relationship system while holding beliefs that are different than the shared beliefs of the congregation. There is wide variation in the flexibility of congregations to think differently about certain beliefs while staying connected.

Dr. Murray Bowen described what he observed as a life force for togetherness that is common among all humans and all of life. It is a counter-balancing force to individuality which is the effort to think, feel and act for oneself. The force for togetherness disrupts this effort in favor of fusing together the thinking, feelings and actions of the group (in this case a congregation but also includes the family).

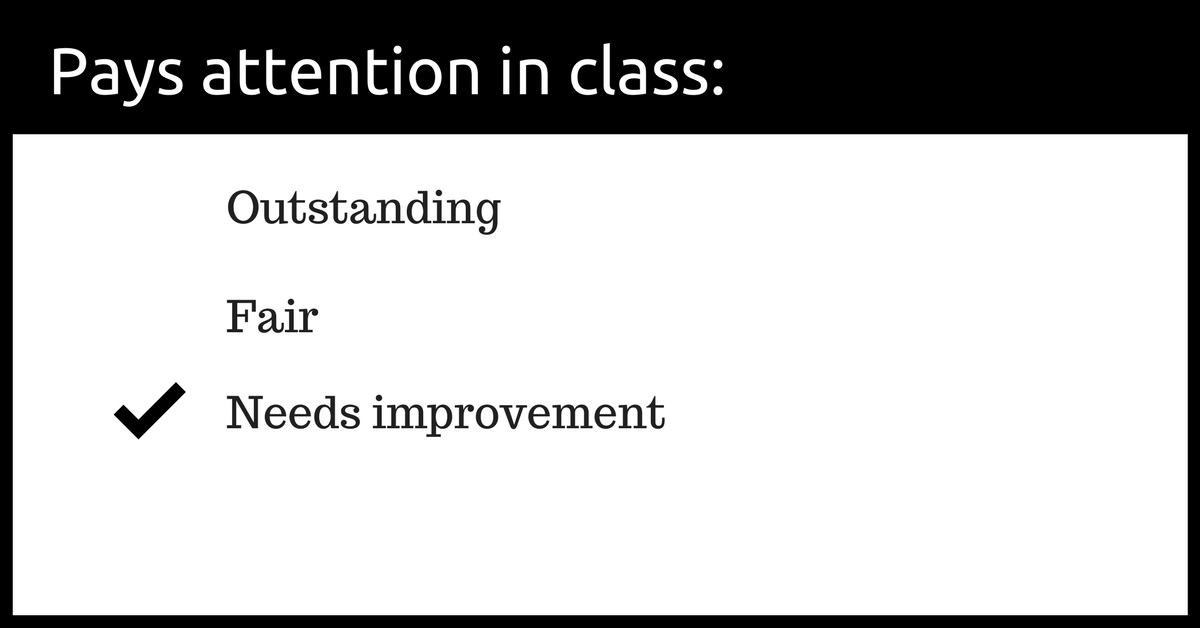

The extent to which a congregation can be at ease with variation in beliefs among congregants is dependent on, among other things, the level of chronic anxiety in the congregation. The higher the level of anxiety, the more likely there will be demands for everyone to agree with what I’m calling shared beliefs. At this elevated level, there is little room for disagreement. People’s thinking becomes fused. When leaders insist that everyone think the same way about God and issues of faith, it’s a good indicator of the level of tension in the congregation and the chronic level of anxiety among leaders. Families (of which congregations are a conglomerate of) also experience this phenomenon.

It is true that shared beliefs define a congregation. Even congregations that participate in interfaith opportunities have shared beliefs about interfaith experiences. So, to some extent, there is no escaping the need for shared beliefs. They serve a functional purpose for humans.

The assumption, though, that society will collapse into chaos if people believe and value whatever they want is false. It is a byproduct of anxiety. It is an incomplete understanding of the process of being a good thinker. Supporting an individual’s effort to define and clarify their beliefs does not spur debate, conflict and schism. Societal problems are not caused by “free thinkers.” Societal problems are the result of an over-insistence (an anxious focus) that everyone think the same way. The more congregational leaders demand compliance on specific beliefs and issues of faith, the more revved up and anxious the congregation becomes and vice versa. It can also work the other way. Take for example political coalition building. Bringing together people who think differently can be an anxious process.

The history of humanity is littered with examples of the struggle to either insist that everyone believe the same thing or everyone believing whatever they want. If leaders strongly insist that everyone believe the same way, then people react and demand freedom. If leaders strongly encourage independent beliefs and values, then people clamor for shared beliefs and values.

So, what does any of this have to do with discipleship?

My original intent for this blog was to consider what a robust discipleship program might look like. For now, I believe a robust discipleship program takes into consideration the following:

First, beliefs are inherently caught up in a relationship process. The work of clarifying core beliefs and principles requires an understanding of emotional process. As fear increases, there is a greater demand on individuals in a relationship system to feel, think and act the same way.

Second, it is possible to hold a core belief and engage others who think differently without conflict, debate, and schism. This can happen to the extent an individual works on differentiation of self. When one is working to develop core beliefs and principles one inevitably bumps up against the reactivity in the relationship system. This becomes an opportunity to be both separate and connected, a fundamental aspect of Bowen’s concept of differentiation. Beliefs are not what bring us together. Beliefs are what enable us to be together.

I hope one day to design a class (sooner than later) that will invite individuals to work on defining their beliefs. Such a class will encourage thinking about the following questions:

- Where did a specific belief come from? Self? Others?

- When was the belief adopted?

- How does the belief serve one well?

- When was one unable to live out the belief?

This effort begins with leaders who are good thinkers. Clergy find opportunities through preaching, teaching and conversations to define and clarify their beliefs. At the same time, they invite others to define and clarify their beliefs. How might leaders encourage themselves and others to work on clarifying beliefs?

A marker of progress in this effort is the ability to articulate a belief without feeling compelled to defend or attack others with their belief. A clearly defined belief helps one navigate the problems of life by providing room for flexibility and adaptability as one responds to new challenges.

Dr. Bowen envisioned the theoretical characteristics of a “differentiated” person when he wrote:

These are principle-oriented, goal directed people who have many of the qualities that have been called "inner directed." They begin "growing away" from their parents in infancy. They are always sure of their beliefs and convictions but are never dogmatic or fixed in thinking. They can hear and evaluate the viewpoints of others and discard old beliefs in favor of new. They are sufficiently secure with themselves that functioning is not affected by either praise or criticism from others. They can respect the self in the identity of another without becoming critical or becoming emotionally involved in trying to modify the life course of another. They assume total responsibility for self and are sure of their responsibility for family and society. There are realistically aware of their dependency on their fellow man. With the ability to keep emotional functioning contained within the boundaries of self, they are free to move about in any relationship system and engage in a whole spectrum of intense relationships without a "need" for the other that can impair functioning. The "other" in such a relationship does not feel "used." Family Therapy in Clinical Practice, Page 164

What are the benefits and challenges of developing a discipleship program that encourages and models differentiation of self?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed