Sailors used the Beaufort Scale to measure the force of the wind by observing its impact on water and land. As the wind increased, a sailor could see changes in the behavior of the water and the trees. The scale was from 0 (calm) to 12 (hurricane).

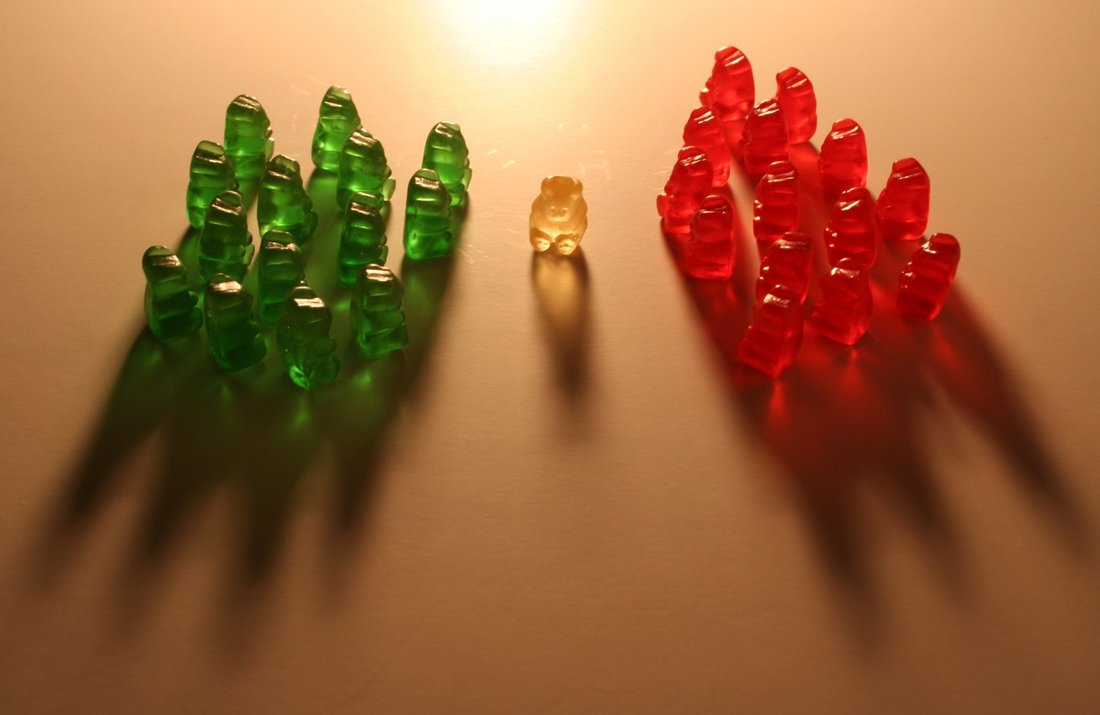

Joseph Liechty and Cecelia Clegg, recently wrote a book, Moving Beyond Sectarianism: Religion, Conflict and Reconciliation in Northern Ireland (2011). Similar to the Beaufort Scale, Liechty and Clegg created a scale to predict the level of sectarian violence. To assess the level of violence they created a scale based on the way separate sects talked about each other. When sects of people are calm, and at peace, their words about other groups are different than when they are at war. Here is their scale:

Scale of Sectarian Danger

Escalation by words and actions

- We are different, we behave differently

- We are right.

- We are right and you are wrong

- You are a less adequate version of what we are

- You are not what you say you are

- We are in fact what you say you are

- What you are doing is evil

- You are so wrong that you forfeit ordinary rights

- You are less than human

- You are evil

- You are demonic

Whether the conflict is in a family around divorce, a congregation struggling with financial issues, or a community engaged in civil unrest the scale illuminates the process of escalation that occurs in relationship systems.

It reminded me of Dr. Murray Bowen’s scale of differentiation . . . A scale of human behavior. Dr. Bowen observed that human functioning could be placed on a theoretical scale between 0 and 100. On this continuum of human functioning, there is wide variation in behavior based on some key variables.

The first variable is chronic anxiety which is a sustained response to fear even when a real threat is not present. Recently, researchers have discovered that during one’s lifetime, genes are turned on and off in response to environmental factors. This process of regulating genes allows humans to be flexible and adaptable in response to their environment. These changes in genetic markers are then passed on from one generation to the next. This process is known as epigenetics.

Changes to DNA that were necessary and advantages in one generation may no longer serve a purpose in the next, but the reactivity stirred in the first generation continues to the next. The result is a heightened level of anxiety (chronic anxiety) in the next generation even though the danger is no longer present. Over time, a higher level of chronic anxiety can lead to physical, emotional, and behavioral problems in subsequent generations.

I don’t know exactly how one would think about the passing of chronic anxiety from generation to generation in a congregation. But I’ve been in enough congregations to know that the narrative the church tells is passed from one generation to the next. Why doesn’t the congregation change the worship times? Because 20 years ago, Mr. Thinksalotofhimself threatened to take half of the congregation with him if the 8:30 am traditional service was moved or canceled. He’s been dead now for 10 years, but the memory and behavior of the congregation from that time (the fear of the threat) continues today in the narrative the congregation tells about itself.

It turns out that relationship systems (whether they are families, congregations, or communities) who have higher levels of chronic anxiety end up lower on the scale of differentiation. Chronic anxiety disrupts the brain's ability to think. It keeps the body in a constant state of over sensitivity to a possible threat. Over time, this raised level of sensitivity takes its toll on the system.

The second variable is stress. It is the level of acute anxiety at a given moment. A stressor could be external to the community or internal. The lower a relationship system is on the scale of differentiation, the more reactive it will be to episodic stressors. Relationship systems lower on the scale (with higher levels of chronic anxiety) only require a small amount of increased stress to create symptoms. Systems that are higher on the scale (with lower levels of chronic anxiety) require a larger amount of stress to create symptoms.

This is why some congregations are able to weather change better than others. In congregations where leaders are lower on the scale of differentiation, they tend to blame people in the congregation or institutional leaders who are outside the congregation. Congregations with leaders that are higher on the scale take responsibility for their situation and work to find solutions to the challenges they face.

The third variable is the availability and use of resources. As congregations are confronted with challenges, the availability and use of resources can make a difference in outcomes. A lower functioning community that has a large number of resources available at its disposal can do better than a higher functioning community that has zero resources. Systems that are cutoff from resources do not fair as well as those with access and use of them.

For most congregations, resources come in three categories: money, volunteers, and leadership. If congregations are good stewards of their money, engage volunteers to use their gifts, and have individuals who are responsible leaders they are well on their way to overcoming the challenges they face. When congregations lack these resources or are not good stewards of them, then they are unlikely to move forward.

Why does this matter? When communities (and here I'm not only talking about congregations but also town and cities, as well as families) face challenges, their level on the scale of differentiation and an analysis of these variables will determine how well a community will do overall and whether or not they will engage in words and actions that will escalate toward violence. If a community typically functions at a higher level, has access to and uses resources, and is facing a very difficult challenge, there is a greater likelihood they will overcome the challenge without resorting to violence (verbal or physical) towards others.

If, on the other hand, you have a community that has a lower level of functioning (a high level of chronic anxiety), has limited access to resources and does not make good use of them, even though the challenge they face may be small, there is a greater likelihood that they will engage in words and actions that have the potential to escalate towards violence.

Without an understanding of behavior on a continuum and an appreciation of the wide variation that exists in communal responses, we will always struggle to understand violence. Once we begin to observe all communities from these various factors, we can better predict which communities are more likely to engage in violent behavior and which communities are more likely to resolve their challenges without resorting to violence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed