And Are We Yet Alive is a classic Methodist hymn, written by Charles Wesley. He wrote it as a gathering song for worship. John Wesley, his brother, incorporated the hymn into the conferences of the Methodist movement. Today, it’s often sung when United Methodist come together for special gatherings.

I once illustrated in a sermon the significance of this hymn in my life. Using sticky notes, I wrote down all the crises and challenges I faced in my life. No matter how great or how small, I wrote down each one. I stuck the sticky notes to my body. I was covered from head to toe in sticky notes! Then I repeated the phrase, “And am I yet alive!” At the time, it was a reminder that, after everything I faced, I was still alive.

All of us experience challenges. The question remains: Why are some people more resilient than others? What does it take to overcome a challenge? I think it has something to do with what we say to ourselves, how we think, and what we do.

What to Say

After I preached that sermon, I changed the way I talked to myself. I started saying things like, “You had faced challenges before and made it through. You will survive this new challenge, just like you have survived everything else.” When I’m stressed, and my mind is revved up, I remind myself, “In a year from now, you won’t remember going through this.” In most cases, that’s true. And when I’m really desperate, my mantra becomes, “This too shall pass.”

What do you tell yourself when faced with a challenge? I ask people this question whenever someone tells me they are facing a challenge. I might also ask, “What helped you get through it? What did you tell yourself?” We all have things we tell ourselves. One exercise to consider is to ask six people you are close to what they tell themselves during difficult times. Make sure to ask family members!

How to Think

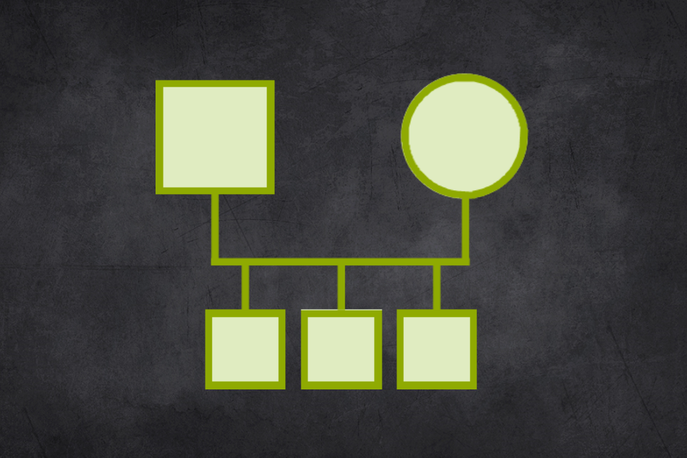

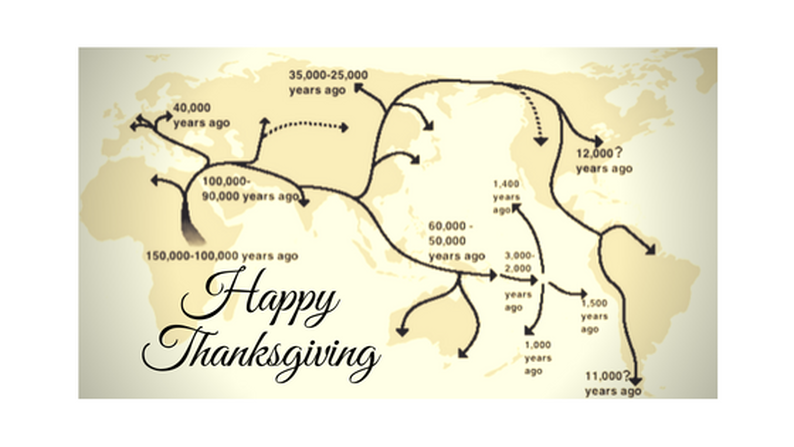

How does one “think systems?” It’s easy to get fixated on one person and see them as the “problem.” We assume behavior is confined to the individual, but it’s not. A systems view of behavior shifts the focus off of the individual and onto the relationship system. For Bowen, the family is the main system. He saw the family, not as a collection of individuals, but as an emotional unit. Each person’s behavior connects to the functioning of the system. When there is a change in the way one person behaves, and the whole family shifts its functioning.

Dr. Bowen developed the family diagram as a way to observe and think systems. Using the format of a pedigree chart, Bowen diagrammed the emotional process within the family unit, including the multigenerational family. By approaching the family as a system, Bowen presented a new way to think about behavior within the context of a family.

This approach is also useful for other systems like congregations, workplaces, and communities. It’s easy to diagnose others or self. Seeing a challenge through a system lens broadens the focus of the problem, reduces the intensity, and provides a pathway for a more mature response.

What to Do

Just to review: learning to function at a higher level involves three basic steps. The first step is to calm down the internal stress response using words and phrases that reorientate the brain towards a more factual perception of reality. The second step is to widen one’s focus and not get caught in a narrow view of the problem. The third step is to take action.

After one calms down and observes the interplay of the relationship system, one begins to “see” the part one plays in the problem. And while it would be much easier to blame others or blame self, the facts speak for themselves. Triangles, the transfer of anxiety, the multigenerational process, and other concepts that Bowen outlined all play a role in how the system functions.

There are multiple options for responding to a problem. If one can observe the system at work and see how one contributes to the system, then one can choose to act differently. Taking an action step requires careful planning. It’s important to predict how others in the system will respond to an action step. It's essential not to react or blame when others are reactive and blaming. To be sure, one can get worked up on the inside during this process. So, it’s important to work at staying calmer. Even if others respond intensely, it’s important to stay in good contact and maintain one’s new position. Eventually, others will come around and accept it. And the system will do better.

Whether the challenge comes from the family, the congregation, the workplace, or the community having a coach can make a big difference. This is not about technique. This is about good thinking. And while there are thousands of blogs out there that will tell you what to do, this approach is about an effort to be a better self in relationship to others. There are concepts to guide one along the way that Dr. Bowen developed. Learning these concepts is one way to become the best person you can be.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed