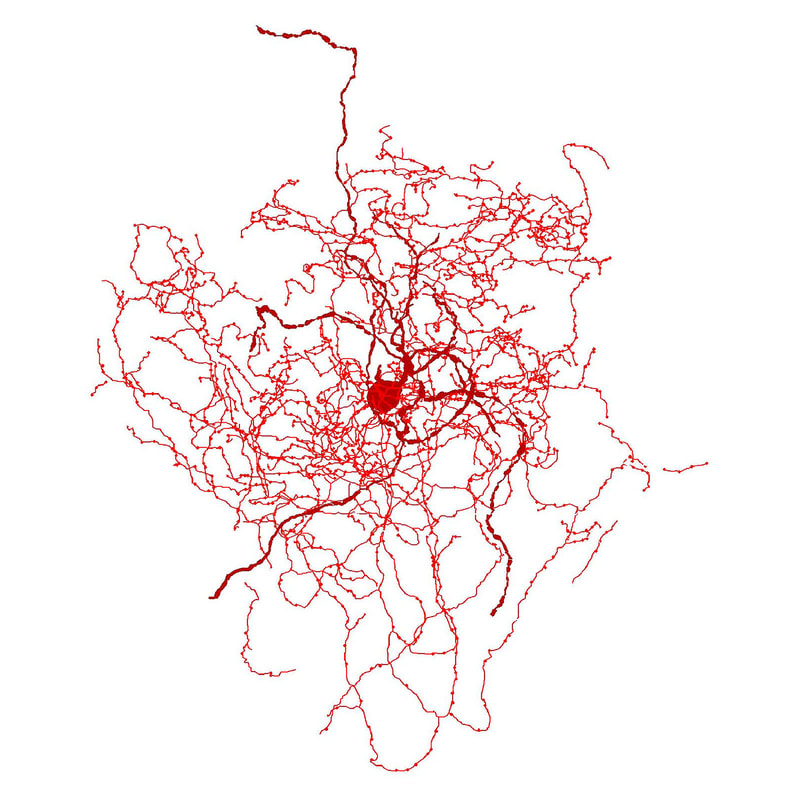

Scientists have discovered a new type of brain cell called the rosehip neuron. The discovery was made by Ed Lein, Ph.D., Investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science and Gábor Tamás. The rosehip neuron may be unique to humans. It has not been found in mice or other animal species.

What’s distinct about the rosehip neuron is its role as a specialized inhibitor. Inhibitors put the brakes on certain signals traveling through the brain. The result is a halting of certain actions and behaviors. Neurons send their signals down the axon of the nerve cell where they release neurotransmitters. Inhibitor neurons send neurotransmitters to other neurons which inhibit their ability to “fire.” Further research is needed to determine what specific behaviors are affected by the rosehip neuron.

As I meditated on the discovery of the rosehip neuron, I began to speculate about its role in the disruption of automatic patterns of behavior. Let’s pretend it’s lunch time but you’ve forgotten to pack a lunch. Your morning meeting went over and it’s now early afternoon. You are famished. You set a diet goal to restrict certain foods. In the drive thru of your favorite fast-food joint, you consider your options. Burger or salad? What makes the difference between choosing a salad or a burger? Or consider this example. I was sitting on a couch petting the cat that jumped into my lap. I was performing the “correct” scratching and petting methods that have proven acceptable to Jorge. There was purring and stretching. All was well. And then he bit my hand. As I checked to see if I was bleeding, I said to Jorge, “You need to make better choices!” What does it take to make better choices? Is the disruption of behavior a human phenomenon or can other animals do it? What makes the difference?

Humans have a unique ability to inhibit automatic behaviors through a thinking system. Moral codes of conduct, beliefs, values and core principles play a role in guiding one’s behavior. Several examples come to mind. The Torah contains the Ten Commandments, which are a list of inhibitors. The second portion of the commandments declare, “you shall not . . .” These early laws (including the Deuteronomic Code) have the potential to inhibit certain automatic behaviors. They command individuals to put the brakes on polytheism, murder, adultery, stealing, lying and coveting.

Similarly, criminal law in the United States is designed to deter certain behaviors. Sentencing guidelines have the potential to inhibit criminal behavior. Murder, for example, is organized by degrees and within these degrees are sentencing guidelines for punishment. Robert Sapolsky in his book, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst discusses how thinking can influence behavior, but admits that processes that favor automatic behavior are powerful and can be difficult to inhibit.

Behavior is a product of the nuclear family emotional process. This process is passed down the generations creating patterns of behavior to manage anxiety, stress and tension in the family. These patterns focus the anxiety of the family onto one person. As anxiety goes up one individual carries the load of anxiety resulting in symptoms. Symptoms can be physical in nature, psychological and behavioral. For example, when a family experiences a stressful event, a family member may attempt to manage the tension by organizing the family. The automatic response of telling others what to do is a behavioral response to the rising level of anxiety in the family. In reaction to the effort to organize the family, others may ignore the commands, become combative or give in and comply. These responses are automatic and reactive because the thinking system in the brain is largely not involved. It is for all intents and purposes offline. Blaming someone for the way they automatically manage stress misses the point that everyone in the family plays a party in how one behaves. One can make a difference in the way they behave, but only when the effort is to work on self.

Differentiation of self is the first step in learning how to put the brakes on automatic, reactive responses to chronic anxiety in the family. The process begins by observing the "who," "what," "where," "when" and "how" anxiety flows through the family. What follows are incremental steps towards understanding how one picks up or passes along the anxiety, discovering more responsible ways for responding to anxiety in self and in others and developing a broader capacity to engage one’s thinking in the midst of anxious others and self.

Perhaps one day scientist will discover the neuronal pathways that lead to better functioning for individuals and for families. It may be that inhibitor neurons play a role in toning down anxious signals by way of higher-level processing. Until we have all the facts we use theories like Bowen family system theory, beliefs and core principles to guide our thinking and behavior.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed