It was the first time I called in sick on a Sunday morning. There was no way I could stand up in front of the congregation. My body was being unusually unpredictable. I had to call someone. I gave them a two-hour notice. As I hung up the phone, my anxious brain (the title of my next book) concocted at least four narratives of how my absence would result in a train wreck. None of them are worth mentioning, although the fear of a mutiny is always in the mix of perceived possibilities.

While I rested in uncertainty, my phone chimed with words of encouragement. The worship services had gone well without me. The person I called on at the last minute did a wonderful job. My anxious brain was wrong.

I felt relieved. Not the kind of relief you get after a long illness or a battle with a disease where you finally start to feel better. It was the relief you feel when your fears are not realized. Those fears, unyoked to any sort of reality, had felt real. Feelings are useful when they provide feedback on how the body is processing anxiety. But I’ve learned through trial and error not to respond to situations solely based on my feelings. That morning, lying in bed and worried sick, my feelings got the best of me.

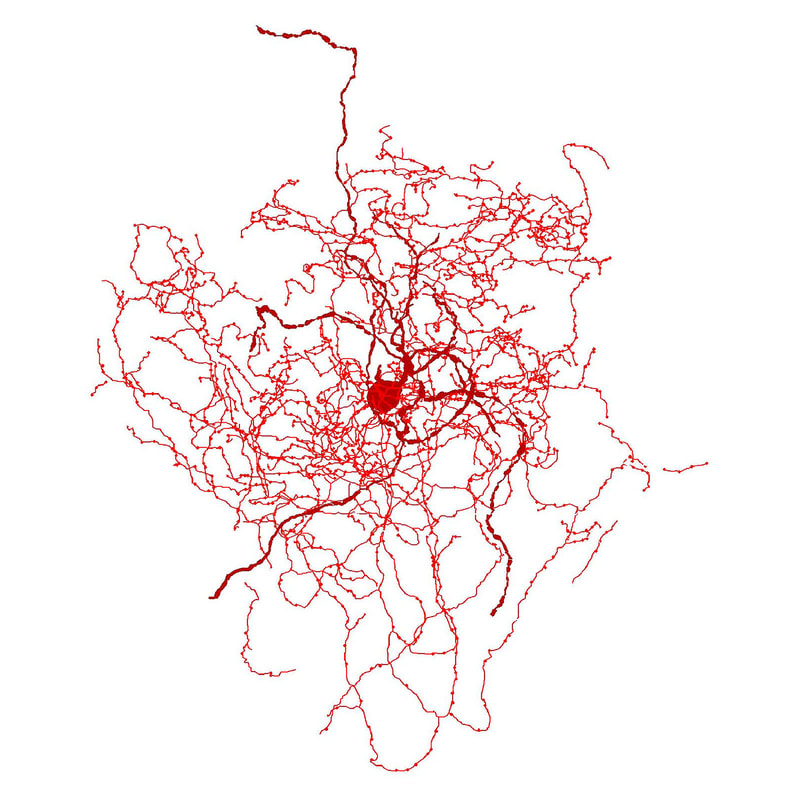

Train wrecks don’t happen because of one person. Likewise, things don’t go well just because of one person. It takes a relationship system to get results, good or bad. Everyone plays a role in how the systems functions. Each person is responsible to the system and it was clear that anxiety led me to think that I was solely responsible.

I realized, as I recovered on the couch, that I am prone to take responsibility for the functioning of a congregational system; a system that is largely out of my control. I cannot be responsible for how a congregation meets a challenge or if it meets a challenge. Congregations do the best they can do. That morning, they did well.

Running into one’s level of worry can feel embarrassing. But if one can observe how one’s level of worry impacts oneself and others in the system, it becomes an opportunity to shift one’s functioning in a more responsible direction. I am grateful for the morning I had to lie still and contemplate this observation.

You might be wondering how I got sick in the first place. Symptoms, like the one I was experiencing, are generated from the family emotional process. To truly understand how symptoms develop, I encourage you to read Dr. Murray Bowen’s book, Family Therapy in Clinical Practice.

Subscribe to receive the newest blog in your inbox every Monday morning.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed